Authors: Mari Toivanen, Päivi Pirkkalainen, Gwenaëlle Bauvois & Viivi Eskelinen

The past year has been peculiar in many respects. Over more than a year ago, many countries in the world put in place COVID-19 related restrictions in response to a rapidly growing pandemic. The everyday lives and routines of millions of people were drastically changed, at the same time as we witnessed the immeasurable loss of lives to the virus.

We, at the editorial board of LYR, have observed how the pandemic affected particularly the migration-related phenomena that our blog deals with. We have witnessed how mobilities and migration, transnational connections and ties, ethnic relations, migrants’ rights and everyday lives have been shaped and affected by the on-going pandemic. The texts in this special issue point to a number of aspects related to migration that have been particularly touched by the on-going pandemic.

Inequalities linked to mobility have become more visible

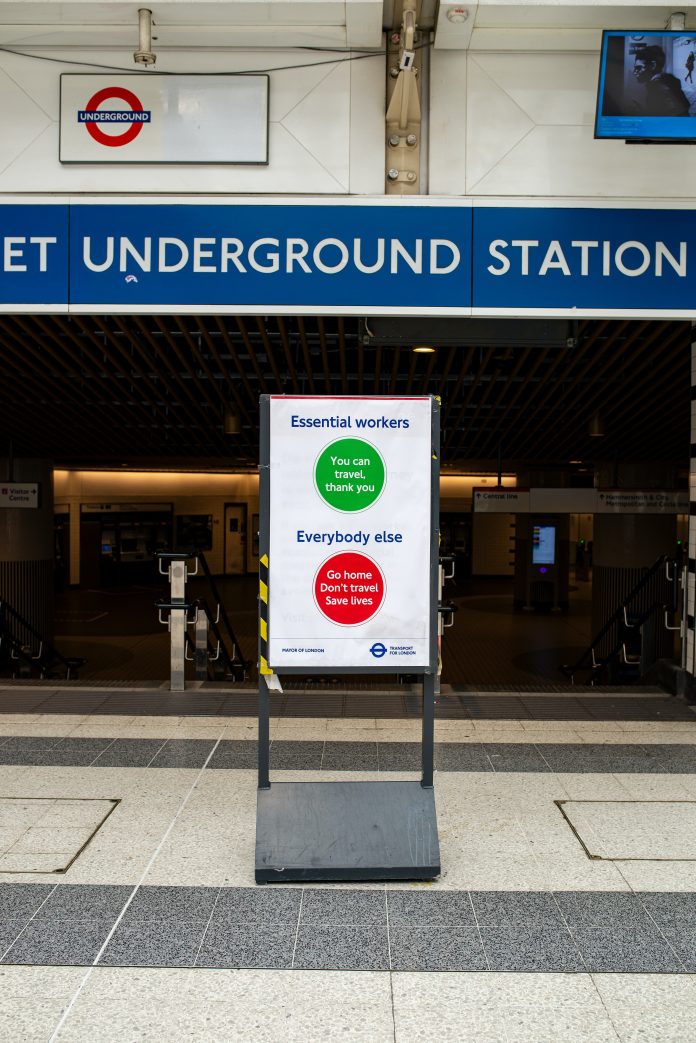

Many countries closed their borders last spring and erected border controls, thus directly impacting how people were able to move across borders. Individuals holding powerful passports and relatively privileged means of being mobile across national borders faced harsher border controls and restrictions to their mobility – an experience that has been everyday reality to less-privileged people across the globe even before the pandemic.

Restrictions affected all kinds of mobilities, from tourism to more or less permanent migratory movements. Restrictions had a direct impact on the lives of individuals who were accustomed to regularly visit family members, work or study across different state borders. Transnational families could not meet family members living across the countries. Seasonal workers in specific sectors and from specific countries could not be hired. Student exchange programmes were largely put to halt and work-related trips cancelled.

As public discussions centre around the issues of mobility of the privileged people, the situation of people in vulnerable situations remains in the shadows. The pandemic has affected the situation in refugee camps struggling with inadequate hygiene and health facilities. Another largely undiscussed issue has been for example the hindrances in the closing of borders presented to asylum-seekers and refugees, or challenges the pandemic has caused to family reunification.

On the one hand, several Western countries have set up travel restrictions, while continuing to deport foreigners. This raises serious concerns about the possible spreading of the virus by deportees to poorer countries which lack health facilities and thus are more vulnerable to the effects of the pandemic.

One solution that has been suggested for restoring mobility (for those in the privileged position to undertake it again) has been the COVID-19 passport, linked to the vaccination. Concerning this, the potential it presents in adding yet another layer in (re)producing inequality in mobility for some, at the expense of others, has been largely overlooked in current political debates. It can add into the pre-existing vulnerabilities for marginalised groups that have hitherto accumulated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Vulnerabilities accumulate and multiply during times of crises

The pandemic has revealed vulnerabilities relating not only to mobilities but also to the (lack of) rights to be immobile. For example, people in a low labour market position working in the service and hospitality sector have no privilege to protect themselves from the virus in doing remote work. The vulnerabilities for migrant communities and their members have accumulated in other respects too. One example are individuals whose residence permits have been linked to their employment status have found themselves in difficult situations as unemployment grew in the spring 2020, for instance in already precarious occupational sectors.

Another example is how neighbourhoods with higher concentration of migrants have been more impacted by the infection rates. This has been due to their inhabitants working in particular sectors that necessitate contact, due to larger family sizes in apartments and due to challenges in accessing country-specific information in one’s mother language. With higher mortality rates due to the virus, one topic that has received less attention are the funeral practices for migrants, whose families have faced challenges in expatriating the deceased back to homeland soil.

Another particularly striking example is how migrant communities and individuals, often of Asian origin have been affected by the rise of xenophobia and racism. The growing anti-Asian sentiment, which has also resonated in political discourses, involves blaming “others” for the spreading of the virus. In short, the pre-existing vulnerabilities have been accentuated due to societies shutting down following restrictions and countries closing their borders.

It is important that even during the pandemic, we pay attention to those in the most challenging circumstances and recognise different communities’ and individuals’ vulnerabilities and forms of resilience. At the heart of this, is listening and providing space for first-hand experiences of such communities and individuals to be heard – even in times of crises. By acknowledging the lived experiences of potentially vulnerable communities and individuals, we can better grasp how societal and political attitudes towards them are shaped through the politics of “othering”. On the flip side of the coin, we can make more visible the existing inequalities by looking at how entitlements and rights operate for the most privileged ones.

The series

This blog text series is focusing on how mobilities, inequalities, discrimination as well as transnational connections are shaped and affected by the ongoing global pandemic, the COVID-19. Five research-based texts focus on the lived experiences and perceptions of and on migrant communities and their members, on diverse challenges they have faced and on how privileges related to mobility look like during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

The series kicks off with the text by Mari Toivanen who discusses how the right to be mobile looks like after COVID-19 pandemic. Her text addresses inequalities in mobility rights by focusing on location-independent workers, digital nomads. Her text points out critical issues in how the post-pandemic situation may lead to even deeper inequalities in the rights to be mobile, for instance, in form of the so-called vaccine passport.

This is followed by Viivi Eskelinen’s text in which she analyses the role of religiosity and different existential threats compared to the disease-related threat of COVID-19. She focuses upon attitudes towards religious out-groups such as Muslims and shows that the threat of a new refugee crisis was associated more consistently with negative attitudes towards Muslims in comparison to threats presented by the COVID-19 pandemic and the climate change.

The next text in line is by Linda Haapajärvi, who discusses how the COVID-19 pandemic has put migrant families in a vulnerable position in France due to their socioeconomic status, inadequate civil rights and families’ cross-border practices. She showcases this by introducing the story of Ibrahima, whose father passed away to the virus in 2020, and whose family’s mourning process is hindered by the difficulty to expatriate his father’s remains back to his home country, Senegal.

The following text is by Jaana Palander, who describes the challenges that transnational families have faced during the pandemic. She discusses how mobility restrictions have impacted families who live apart from each other. In her text, she also critically assesses how proportionate restrictions are from the point of view of transnational families.

Finally, the blog series is concluded by Eerika Finell, who writes about the experiences among Somali, Russian and Arabic speaking minorities during the first wave of the pandemic. She shows that Arabic, Somali, and Russian-speaking migrants in Finland were stressed not only by the pandemic situation in Finland but also in their home countries. Showing that they were satisfied with cooperation within the community and the communication between local authorities and migrant communities, Eerika Finell shows that by taking care of the more vulnerable communities, we can foster positive experiences within these communities.